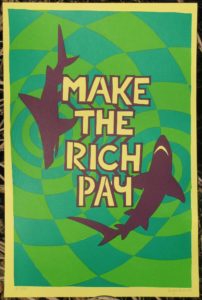

Today is a horrifying holiday dedicated to false narratives that attempt to cover over colonialism and genocide, and also a day when many people make an effort to “give back” by volunteering somewhere. Images of friendly upper class people volunteering at soup kitchens to feed homeless people articulate charity narratives that hide the actual causes and consequences of wealth and poverty.

I am sensing, all around me these days, how desperately frustrated, scared, and angry many people are about what is going on in the world around us–climate change, war-induced famine in Yemen, imprisoned children and parents at our borders and across the land, Amazon’s takeover of our food systems and cities, superstorms and disastrous fires, and so much more. I think a lot of people are wishing they knew more about how to plug in to processes of change they can believe in. I am frustrated watching misunderstandings about what change is and how it happens (“Care about poor people? Just volunteer in a soup kitchen once a year!”) circulate widely. I think their circulation is designed to demobilize us and keep us from participating in effective strategies to build the social conditions we want and need. So here is a very rough draft of a chart and some writing about the difference between “having a cause” as it is commonly described (or worse yet, the careerist version, “social justice entrepreneurship”), and living a life focused on our commitments to radical transformation. I hope it helps us imagine more creative, robust ways of being engaged with each other and the conditions we live in as we participate in resistance and transformation.

“Having a Cause” versus Living in Alignment with Our Values

|

Activism as career, hobby, or volunteering for “a cause” |

Living in alignment with your passion and an ethical belief about how the world could be |

|

Get trained as professional to work for a non-profit. |

Try to find a way of getting by that is interesting and not too compromising and gives maximum time for participation in what I really believe in. |

|

Volunteer hours for a non-profit (until I get too busy at a job or with kids). |

Be part of organizations and projects that I am intimately connected with, foster deep relationships with the other people in those orgs and projects, continue for years. |

|

Have a pet “cause” that I care about, its part of my personality or public image. |

Have passionate convictions, study what social movements have done and are doing about what I care about, look for connections to other areas of mobilization and study those too. |

|

Most of my friends, social activities, most parts of my life don’t relate to my “cause”—it is something I do on the side of my normal life. |

Shared beliefs about the world is one of the key reasons I choose my friends and the spaces I want to participate in, I am not willing to box up my principles and beliefs to fit in to social scenes, I am most excited by other people who are also driven by a passion for justice. |

|

Finding one way to “give back” is enough—donating some money or time—to be above reproach and feel good about my role in the system (and defensive if anyone suggests I might have more to learn or do). |

I feel enlivened by my participation in resistance work, but I never feel finished. I remain open to learning new things about the systems I live under and my complicity in them, always looking for new ways to bring my whole self into alignment with what I believe is right. |

The systems we live under are focused on keeping us in our places and keeping the status quo going strong. That means that our resistance, frustration or sense of injustice needs to be channeled in ways that will make it minimally disruptive. Our sense that things are not right, that it is unjust for some people to have so much more than they need while others die of malnutrition and exposure, could be threatening if we got together to overturn a system that keeps concentrating wealth. That system would prefer that we go back to jobs that keep churning out that wealth for the top 1%, and volunteer at a soup kitchen on Thanksgiving, and feel like we have satisfied our concerns about poverty. That same system constantly feeds us reasons to believe that rich people deserve to be rich and poor people deserve to be poor, to keep us from feeling the rage and despair that emerge if we really face the severity of contemporary conditions of inequality.

Some people talk about this as a difference between “charity” models and social justice models. Charity models imagine a world in which people give a little of their extra time or money to organizations that provide social services to poor people. Usually those services are moralizing, focused on questions of who “deserves” services and who does not (are you a current drug user? Are you taking your psych meds? Are you a parent? Do you have lawful immigration status? Do you have any felony convictions? Did you come to all three appointments on time? Are you “housing-ready”? Are you “job-ready”?). Charity is system-affirming. It does nothing about the root causes of poverty, criminalization, and racism. It just treats a few of the symptoms selectively. Social justice work is about making it so that no one is poor, homeless, targeted by police, deportable, or exploited. Looking at the chart above, we can see that most of the assumptions about justice work that reside in the left hand column are imagining a system in which our interest in resistance gets channeled toward a charity model. The description of a life focused on living in alignment with our values, in the right hand column, is both broader and deeper, and it allows our care for other people and the planet to animate our entire lives. This is a taller order, a bigger engagement, a higher bar, a deeper commitment. It is also a greater form of aliveness, a chance to be on an endless passionate quest with others, seeking awareness and alignment rather than complacency and a minimal nod to our concerns about what is happening.

Thin notions of volunteerism are about “feeling good” by “giving back.” I would argue that we need to feel more of the feelings that are labeled negative, like grief, sadness, anger, rage, and despair. There are so many good reasons to feel those things, because shit is fucked up, and we are living with our own experiences of harm and violence and with witnessing the harm happening at intimate and planetary scales all around us. Consumer culture wants to keep us numb, and many of us feel so overwhelmed that we can’t imagine how we would begin to do anything effective. It can feel like the safest bet is to not even try. Or it can feel like we should go with a prescribed recipe for participating in charity or social services—volunteering at a soup kitchen on Thanksgiving, or attending one march or rally a year. Often these are efforts to quell the guilt and concern that plague us, rather than providing real opportunities for connection where we feel like we were part of meaningful change. In my experience, it is more engagement that actually enlivens us—more curiosity, more willingness to see the harm that surrounds us and ask how we can relate to it differently.

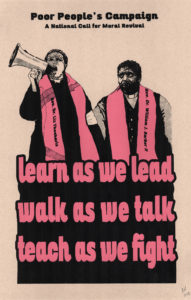

When I first found people who lived this way, I was astounded. I learned so many things. I met friends who rode bikes and worked to make transportation options not center fossil fuels. I met people who composted their food scraps, and avoided food waste, and worked in community gardens, and fought for more justice in food systems. I met people who worked for gender equity in their household labor arrangements, and were trying to raise their kids without enforcing patriarchal gender norms, and were trying to change how gender norms were enforced in their local schools. I met people who were trying to build interpersonal skills and capacities in themselves and their friend groups for conflict resolution, and were building alternatives to calling the police in their communities, and were fighting against jail and prison building in their counties and states. All these people had areas of focus in their work, and were working to line up the details of their day-to-day decisions about eating, transportation, washing the dishes, and how they treated people they knew and strangers, with their values. But their personal day-to-day decisions were not just guided by the main area they worked on. A person who was working against policing and prisons was also, I found, composting their food scraps, boycotting union-busting corporations, participating in a care collective for a chronically ill friend, showing up to the mobilizations against evictions in their neighborhood. I found people who worked to let their values guide every part of their lives, not because they believed they could get it right or be perfect or find a way outside the systems and economies we all live under, but because it was pleasurable and meaningful to keep finding that alignment and practicing it.

When people are doing this, it is almost always a collaborative process. We model things for each other, we learn from each other about ways the system is playing out that we had not been aware of. We are interested in each other’s practices, not because we will do them all (not everyone will ride a bike, or install a greywater system where they live, or grow food) but because they are sources of inspiration as we try to build ways of living that are intentional. We give each other courage to look at the realities of systems we are living under, and we make it seem possible to resist what would otherwise seem overwhelming. We co-create new possibilities. Sometimes this means we create incremental steps—is there a way I can consume less fossil fuels if not none? Can I reduce my connection to corporate banks, if not eliminate it? Can I help support some people facing eviction in my city, even if I can’t show up for everyone being harmed by the housing crisis? The perfect is the enemy of the good. This is especially true where we feel immobilized by overwhelm, unable to begin to align ourselves because we feel how extremely out of line our lives are from our principles. Letting ourselves feel the dissatisfaction, frustration, powerlessness that contemporary systems can create is an important part of finding ways to take action towards alignment, finding company on that journey, beginning to take the risk of wanting and acting toward greater alignment. It means being open to the reality that, under these systems, we won’t soon reach a point where we are beyond complicity, living in some perfect, pure way. We will have to endure the pain of living in the contradictions. But the creative process of finding ways toward greater alignment, alongside companions, is so much more pleasurable and alive than suppressing the desire for alignment or doing a token charity gesture to justify complicity.